Throughout the last several years, scientists have been debating whether there is a reproducibility crisis in biomedical research. It’s no surprise: how often are you able to repeat the exact results of your own experiments, let alone those from another lab? Sure, there’s a certain amount of variability given the nature of complex cellular systems. However, if the idea is to use these findings for something bigger, then reproducing results is critical. So, why does it appear that results can’t be corroborated very frequently? And how big of an issue is it really?

Throughout the last several years, scientists have been debating whether there is a reproducibility crisis in biomedical research. It’s no surprise: how often are you able to repeat the exact results of your own experiments, let alone those from another lab? Sure, there’s a certain amount of variability given the nature of complex cellular systems. However, if the idea is to use these findings for something bigger, then reproducing results is critical. So, why does it appear that results can’t be corroborated very frequently? And how big of an issue is it really?

Why is it so hard to reproduce others’ results?

The answer to this question lies in how hard it is to reproduce your own lab’s results. Think of all the times you had to repeat someone’s experiment, either because that person had finished their degree or if you needed to use their previous results as a control to make sure your own experiment works. To perfectly reproduce an old colleague’s results, you would have to sift through endless lab books, including hopefully their SOPs, repurchase reagents that previously expired, and, once you have most (but never all) of the details, hope that the batches of cells or the mice you’re using retained the same characteristics they had when your colleague worked with them. Now imagine doing the same thing for a study that took place outside of your academic institution, where the paper only lists half of the reagents used and doesn’t fully explain any of the protocols. Continuity is difficult to maintain, particularly in an environment where most scientists only work for a few years before leaving the lab. One group even found that, when trying to contact the investigators of 500 original articles, only 25% said they kept their data, while 25% of authors were nowhere to be found, period.1

The scope of the problem

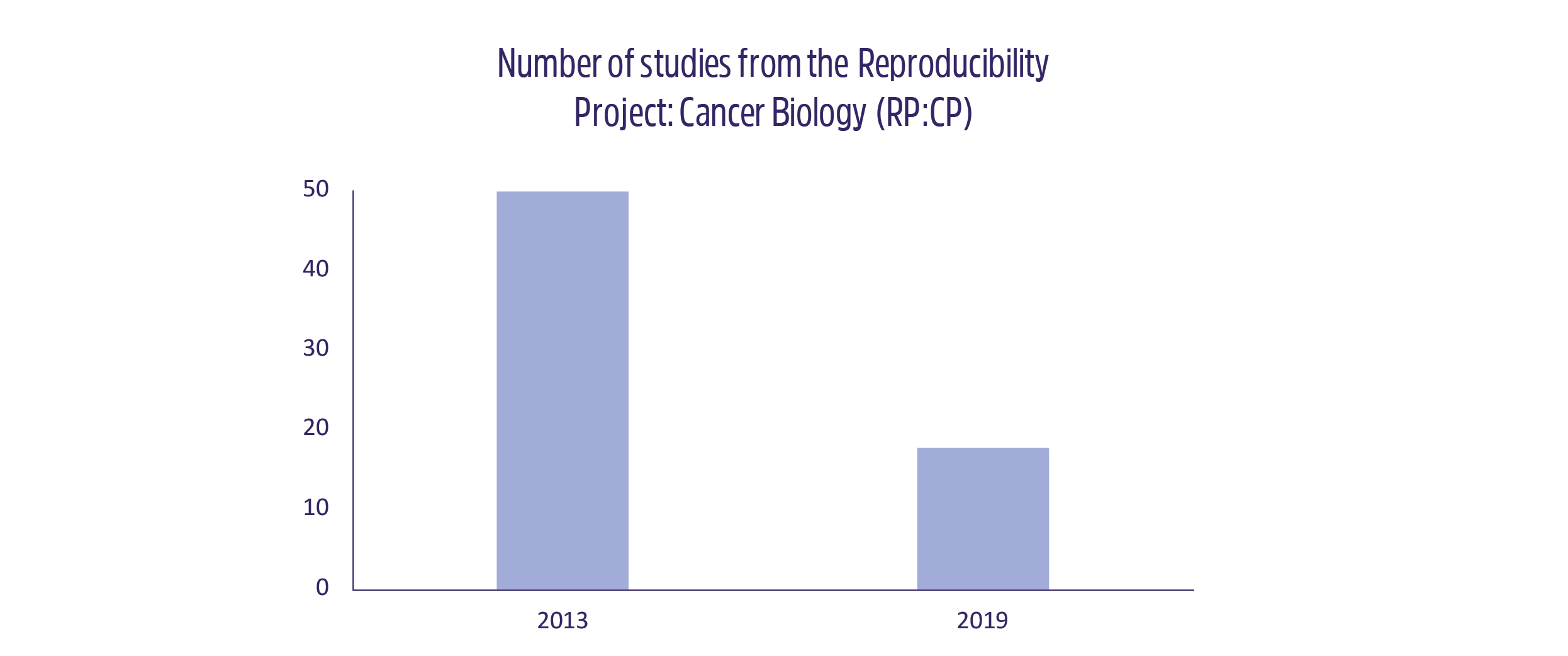

It’s impossible to know which studies are trustworthy in the realm of science until others try to repeat their findings. Some have taken the initiative to assess whether the supposed “reproducibility crisis” is real by attempting to reproduce the results from a handful of high-impact articles. In 2012, C. Glenn Begley and his team at Amgen tested the results of 53 papers and showed that only 6 (11%) of them were reproducible.3 One year earlier, scientists at Bayer found that only 35% of the studies they tested could be reproduced in their entirety.4 One of the larger initiatives of the last few years is the Reproducibility Project: Cancer Biology (RP:CP), which aimed to reproduce the findings from 50 big cancer papers. It began after two pharmaceutical companies complained that they couldn’t repeat the findings of several cancer studies. The project was funded with around $25,000 per study and was expected to only last 1 year. Unfortunately, that number has dwindled down to just 18 studies since the project began in 2013. Why? The same problems that plague the average scientists crept up, making it impossible to repeat several of the studies: more funding was required than originally thought, original materials were unavailable or in poor condition, and it was nearly impossible to recapitulate the protocols used in the original articles because of lost information. On top of that, only 5 of the 10 repeated studies published from the RP:CP were mostly repeatable.1,5

It’s impossible to know which studies are trustworthy in the realm of science until others try to repeat their findings. Some have taken the initiative to assess whether the supposed “reproducibility crisis” is real by attempting to reproduce the results from a handful of high-impact articles. In 2012, C. Glenn Begley and his team at Amgen tested the results of 53 papers and showed that only 6 (11%) of them were reproducible.3 One year earlier, scientists at Bayer found that only 35% of the studies they tested could be reproduced in their entirety.4 One of the larger initiatives of the last few years is the Reproducibility Project: Cancer Biology (RP:CP), which aimed to reproduce the findings from 50 big cancer papers. It began after two pharmaceutical companies complained that they couldn’t repeat the findings of several cancer studies. The project was funded with around $25,000 per study and was expected to only last 1 year. Unfortunately, that number has dwindled down to just 18 studies since the project began in 2013. Why? The same problems that plague the average scientists crept up, making it impossible to repeat several of the studies: more funding was required than originally thought, original materials were unavailable or in poor condition, and it was nearly impossible to recapitulate the protocols used in the original articles because of lost information. On top of that, only 5 of the 10 repeated studies published from the RP:CP were mostly repeatable.1,5

Addressing the problems with reproducibility in academia

The RP:CP was funded, in part, by Science Exchange, headed by Elizabeth Iorns in Palo Alto, California.1,5 Science Exchange also launched a “Reproducibility Initiative” in 2012 with the goal of having scientists validate their work using independent labs. Regrettably, after four years, no one had taken up the offer, most likely because they feared being seen as misusing grant money by double-checking their results.1 Jeffrey S. Mogil and Malcolm R. Macleod, neuroscientists at McGill University and the University of Edinburgh, respectively, have suggested that all animal studies for disease therapies undergo a “preclinical trial,” where the main ideas of each study are independently verified using stringent statistical methods and rigorous experimental design (e.g. blinding and randomization).6 The technology transfer offices (TTOs) of universities, which handle the commercialization of new technology, have also been floated as a means to increase reproducibility, as they can be used to fund external labs to verify results.4

The main drawback of all these options is that repeating experiments requires large amounts of money. Some aren’t convinced that there is a problem with regards to a reproducibility crisis either, but there are still many ways researchers can improve the validity of their own results without the need for independent verification.2 Using a higher statistical threshold would make it more likely that your results are repeatable and submitting more detailed protocols to academic journals would make it easier for scientists in other labs to confirm your research. It’s understandable that not everyone has unlimited resources with which to repeat experiments, but we can all do our part by examining how studies are performed and make them as efficient and technically consistent as possible. Simply keeping a clear, legible record of all your samples, cell lines, and experimental results using a laboratory information management system, combined with barcode labels, goes a long way towards others in your lab being able to repeat your initial findings.

LabTAG by GA International is a leading manufacturer of high-performance specialty labels and a supplier of identification solutions used in research and medical labs as well as healthcare institutions.

References:

- Engber D. Cancer Research is Broken. Slate. April 2016:1-11.

- Fanelli D. Opinion: Is science really facing a reproducibility crisis, and do we need it to? Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2018;115(11):2628-2631.

- Begley C, Ellis L. Raise standards for preclinical cancer research. Nature. 2012;483:531-533.

- Owens B. Reliability of ‘new drug target’ claims called into question. Nature. September 2011:1-5.

- Kaiser J. Plan to replicate 50 high-impact cancer papers shrinks to just 18. Science (80- ). July 2018:1-13.

- Mogil J, Macleod M. No publication without confirmation. Nature. 2017;542:409-411.