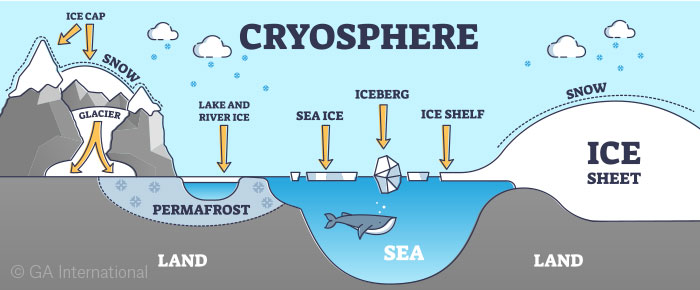

Permafrost in the Arctic has come under sharp focus over the last decade as climate change has rapidly increased its thaw rate and consequently released heavy amounts of gasses, such as methane, into the air. Another consequence of the thawing permafrost is the release of ancient organisms into our “new” environment, among them bacteria, viruses, fungi, and worms. With COVID-19 still lingering among the world’s population, it’s worth exploring what kinds of organisms have been found to date and what that might mean in the near future for human health.

Permafrost viruses are alive and well

The Arctic frost has been well established to help preserve valuable plant samples. In 2014, Dr. Jean-Michel Claverie published one of the first studies to isolate and revive viruses from the permafrost. His group brought 30,000-year-old permafrost samples from Siberian to their lab and isolated and infected amoebas with a new type of large DNA virus he named Pithovirus sibericum.1 A year later, he performed a similar experiment, infecting amoebas with another new giant DNA virus, Mollivirus sibericum, providing evidence that viruses survived relatively well in the permafrost.2

This year, Dr. Claverie’s group published an update on his group’s previous studies, showing that 13 new viruses belonging to seven different clades discovered in the permafrost could infect amoebas. Though Dr. Claverie states in his paper that his research tends to bias large DNA viruses unlikely to infect human cells, he posits that small mammalian viruses hidden in the permafrost are also likely to be present and could potentially revive upon thawing.3 One possible reason Dr. Claverie did not actively search for human viruses is the safety risks of handling potentially fatal human pathogens. However, another group led by scientists from Thompson Rivers University and the Pacific Northwest National Lab showed in 2022 that many families of viruses with eukaryotic hosts were found in permafrost samples, including viruses from Coronavirus and Hantavirus families.4

Interestingly, others have demonstrated a precedent for retrieving confirmed pathogenic viruses from the permafrost. In a series of lengthy expeditions and laboratory experiments dating back to 1995, the flu virus that had caused the 1918 pandemic was obtained from the lung tissue of a patient frozen in the permafrost and subsequently reconstructed. In doing so, scientists were able to infect mice with viral vectors containing one or more genes produced by the 1918 flu virus, which led to widespread bronchial and alveolar necrosis and inflammatory infiltration in the animals. Though these mice weren’t directly infected by viral particles from the permafrost, the particles were intact enough to yield pathogenic RNA sequences.5

Ancient antibiotic resistance

With the COVID-19 pandemic largely in society’s rearview mirror, one of the next significant challenges to our health may come from antibiotic-resistant bacteria. These bacteria are already prevalent worldwide, accounting for increasing disease burden, mortality rates, and hospitalizations. Though many have curtailed antibiotic use in clinical practice, it is still present in the environment through exposure to pollutants and horizontal gene transfer of resistance genes from one species to another. With that in mind, several scientists have tried and succeeded in characterizing antibiotic resistance in bacteria from the ancient permafrost.6-8

Each of three groups—one from the University of Alaska Fairbanks, one from the Karolinska Institutet in Sweden, and one from Aix Marseille Université in France—managed to culture various bacterial species from the permafrost, including numerous strains of staphylococci, pseudomonas, and bacillus. The groups all performed genome sequence analyses on the bacterial strains, showing that many of the species carried genes related to antibiotic resistance, a finding that suggests antibiotic resistance predates the modern use of antibiotics in agriculture and health. After “resuscitating” the bacterial strains, two of the groups confirmed that all strains could, in fact, resist at least one type of commonly used antibiotic.6-8

Ultimately, it appears climate change is here to stay, and with it will come continuous permafrost thawing and more interest in the microorganisms that it harbors. With so little known about what’s inside the permafrost, it not only represents a new and intriguing ecosystem to study but also an area that may require updating biological safety protocols and risk assessment for both old and new viruses and bacterial species.

LabTAG by GA International is a leading manufacturer of high-performance specialty labels and a supplier of identification solutions used in research and medical labs as well as healthcare institutions.

References:

- Legendre M, et al. Thirty-thousand-year-old distant relative of giant icosahedral DNA viruses with a pandoravirus morphology. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(11):4274-4279.

- Legendre M, et al. In-depth study of Mollivirus sibericum, a new 30,000-y-old giant virus infecting Acanthamoeba. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;112(38):E5327-E5335.

- Alempic JM, et al. An Update on Eukaryotic Viruses Revived from Ancient Permafrost. Viruses. 2023;15(2):564.

- Wu R, et al. RNA Viruses Linked to Eukaryotic Hosts in Thawed Permafrost. mSystems. 2022;7(6):e0058222.

- Taubenberger JK, et al. Discovery and characterization of the 1918 pandemic influenza virus in historical context. Antivir Ther. 2007;12(4 Pt B):581-591.

- Kashuba E, et al. Ancient permafrost staphylococci carry antibiotic resistance genes. Microb Ecol Health Dis. 2017;28(1):1345574.

- Afouda P, et al. Culturing Ancient Bacteria Carrying Resistance Genes from Permafrost and Comparative Genomics with Modern Isolates. Microorganisms. 2020;8(10):1522.

- Haan TJ, Drown DM. Unearthing Antibiotic Resistance Associated with Disturbance-Induced Permafrost Thaw in Interior Alaska. Microorganisms. 2021;9(1):116.