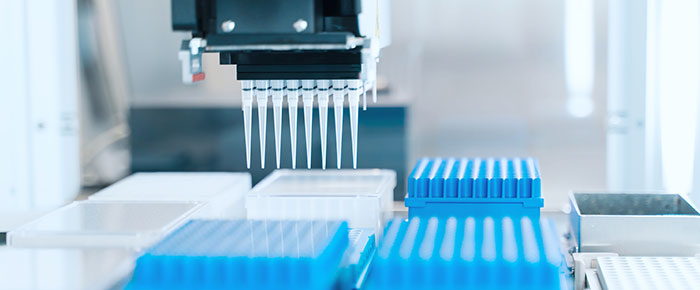

Automation is an emerging trend in the healthcare field that has the potential to positively impact patient service, lab productivity, and staff safety. In addition, automation in the clinical laboratory can allow process standardization which, in turn, may decrease the frequency of outliers and errors.

Development of analytical automation

The primary use for automation in clinical laboratories is to aid in running analytical instrumentation. The first automated analyzer was procured by a clinical chemistry lab in 1956 that could analyze a limited number of samples for analytes such as urea, glucose, and calcium1. This would eventually evolve into the continuous flow auto-analyzers that could process 150 samples an hour, with a database of 20 analytes. Over time, advancements in software and technology have led to each new generation of instruments elevating the throughput and increasing the assay menu.

In the 1970s, laboratory information systems (LIS) and other lab management systems began to be developed and paired with analytical automation, connecting electronic data management and laboratory instrumentation1. This led to a significant increase in sample throughput, which allowed work on the automation of the pre- and post-analytic laboratory work phases to be done. This can encompass various laboratory workflows, including transferring samples to the lab, accepting clinical specimens, as well as the pre-testing, testing, and post-testing processes.

Modern instrumentation in clinical labs can have a variety of configurations in order to perform a range of tasks and analyses.

- Batch Analyzers – The instrument will perform a single test on a group of samples.

- Sequential Analyzers – Samples are tested sequentially, and the results are reported in that same order.

- Continuous Flow Analysis – In continuous flow, liquids are pumped through a system of continuous tubing. Samples are introduced sequentially, following each other through the same network.

- Random Access Discrete Analysis – This allows a variety of tests to be performed on any given number of specimens in any order at any time. Each sample is also analyzed in a distinct reaction vessel.

Advantages of automation

Laboratory automation is classified according to the complexity of the instruments integrated into the process, and can range from no automation, to partial automation, and finally total laboratory automation (TLA). In no automation, all analyzers exist as stand-alone machines, while for partial automation, certain analyzers are interconnected and partially integrated with preanalytical workstations. In clinical labs that have implemented total automation, most analyzers performing different types of tests on various sample types are physically integrated. In addition, many preanalytical and post-analytical steps are automatically performed in workstations that are physically connected with the analyzers and efficiently managed by software programs2.

One of the primary advantages of clinical automation is the lower long-term costs. Several case studies have demonstrated that an efficient TLA model can successfully lower lab costs. This is achieved by a reduction of the manual workforce and due to lower preanalytical and post-analytical expenditures. Moreover, the decrease in required personnel may also reduce lab congestion, while an optimized layout of integrated workstations would minimize technician movement and the need for staff to move around the lab in order to perform multiple analyses on different instrumentation2. Furthermore, an efficient TLA model would effectively reduce turnaround time and simultaneously increase laboratory productivity and throughput. In addition, with the incorporation of a LIS or LIMS, sample management within the system becomes more efficient, with sample locations marked for automatic retrieval in case they need to be re-analyzed. This improves specimen traceability as well by enabling the digital tracking of all processes a sample has been subjected to.

Beyond efficiency and traceability, TLA also improves experimental reproducibility by enhancing standardization and record keeping2. It can help maintain the quality specifications of assays, monitor calibrators, and improve the quality and stability of reagents. The increased accuracy and repeatability throughout the testing process would also benefit assay standardization and simplify certification and accreditation procedures. Automating manual activities can also benefit the quality of the testing process by lowering the risk of diagnostic errors caused by manually-intensive tasks and by performing quality assessments and monitoring specimen integrity. In addition, TLA can help reduce the number of tubes required for a given test, thereby reducing the total volume needed and generating less biological waste.

Potential limitations

Investing in a TLA solution also has certain limitations that need to be accounted for. The primary drawback for most labs is the elevated implementation costs. While a TLA will save a lab money in the long-term, it can be expensive in the short-term. This can be tied to installation costs, the need to purchase new hardware, and the time required to train staff. This can be especially problematic for clinical labs on a fixed budget. Moreover, implementing new hardware can also result in additional costs for running the system, supplies, and maintenance. Additionally, new hardware will necessitate certain space requirements, which may already be in limited supply. When configuring the new installation, ensure analyzers are in an orientation that allows access for maintenance and repair. Flexible TLA models may be preferable when implementing an ideal solution is not possible.

Some additional limitations that may arise include the risk of greater downtime. The higher the complexity of the system, the greater the risk of a system failure causing work to grind to a halt. This is especially true for labs that use vast TLA models, utilizing many connected analyzers. The potential for bottlenecks is also an issue when using TLA. The larger the volume of routine testing, the greater the risk of creating bottlenecks, which may reduce system productivity and turnaround time2. Another potential drawback of clinical automation is the disruption of specialized training for staff. While automation will allow a well-trained employee to perform multiple tasks in a range of sectors, this can have as a side effect that they might become less specialized in a particular field of research. This has its advantages and negatives and should be considered before implementing a TLA or making changes to your workforce.

Automation represents one of the most significant breakthroughs in the field of laboratory diagnostics in recent history. However, there is no one-size-fits-all approach to implementing automation in the clinical lab. As such, time and thoughtful consideration must be given when selecting the optimal automation solution for your lab. While having the potential to be an integral part of any lab’s operation, determining if full clinical automation is required or if a semi-automated solution would be best. Overall, TLA offers the opportunity to connect multiple analytical machines in an effort to improve efficiency, organization, quality, and safety while also providing a significant return in investment in the long-term.

LabTAG by GA International is a leading manufacturer of high-performance specialty labels and a supplier of identification solutions used in research and medical labs as well as healthcare institutions.

References:

- Automation in the clinical laboratory: integration of several analytical and intralaboratory pre- and post-analytical systems. Bakan Ebubekir, Ozturk Nurinnisa, and Kilic-Baygutalp Nurcan. Turk Jour of Biochem, 2017 Jan 20; 42(1):1-13.

- Advantages and limitations of total laboratory automation: a personal overview. Giuseppe Lippi, Giorgio Da Rin. Clin Chem Lab Med, 2019 May 27;57(6):802-811