Barcodes are one of the best ways to track and trace items. They’re found everywhere, in supermarkets, industrial warehouses, labs, and medical facilities. However, barcodes didn’t just appear out of nowhere; a lot of time, effort, and hard work went into their initial development. Here’s the history of barcodes, including how they were first designed and patented more than 70 years ago.

Barcodes are one of the best ways to track and trace items. They’re found everywhere, in supermarkets, industrial warehouses, labs, and medical facilities. However, barcodes didn’t just appear out of nowhere; a lot of time, effort, and hard work went into their initial development. Here’s the history of barcodes, including how they were first designed and patented more than 70 years ago.

The First Barcode

The history of barcodes dates to before World War II, with a mention in a 1934 patent by John Kermode, Douglass Young, and Harry Sparkes. Assigned to the Westinghouse Electric Co LLC, the patent was for a machine that sorted cards and recorded data, which utilized “photo-electric cells or other light-responsive means…in accordance with the marks on the cards or records.” Unfortunately for Westinghouse Electric, the first actual barcode prototype would only be designed 15 years later by Bernard Silver and Joseph Woodland, a pair of graduate students from the Drexel Institute of Technology in Philadelphia. A local grocery store had asked the institute about developing a system that could automatically scan product information. The two students accepted the challenge and began working on a method that used ink patterns, which would glow under UV light. They built something that worked, but because the ink was unstable and expensive, they quickly ditched their first idea. Using some stock market earnings, Woodland continued to find solutions to the problem, working out of his grandfather’s apartment and quitting his teaching job at Drexel.

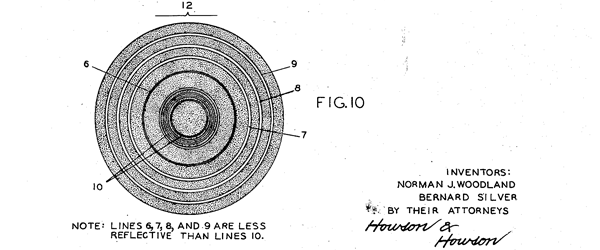

In 1949, Woodland filed a patent for what would eventually become the modern barcode. However, his original design didn’t bare much resemblance to the UPC barcodes of today. Instead, his design used concentric circles, similar in appearance to a bullseye. The pattern was based off Morse code, with four white lines on a dark background. Information was coded based on the presence or absence of any of the white lines, yielding 7 different categories of products that could be identified. More lines could be added, increasing the ability of the code to classify things. For example, a bullseye of 10 lines could code 1023 different categories.

In 1951, Woodland joined IBM and by 1952, his patent was granted. IBM offered to buy the patent at a relatively low price because they didn’t think Woodland’s idea had long-term sustainability; Woodland rejected the offer and sold the patent to the Radio Corporation of America (RCA) instead.

History of Barcodes – The First Practical Application

Woodland’s bullseye barcode system wasn’t the first practical application of a barcode, even though it was the first successful methodology to be patented and bought out. While RCA didn’t put their system to use until 1967, the railroad industry began using something called KarTrak in the early 1960s. Initially developed by David Collins, KarTrak used a series of 13 red and blue reflective stripes of paint on steel plates. There were “stop” and “start” stripes as well as a 4-digit railroad company identifier and a 6-digit car number. Scanning would occur as each car moved out of the yard on its rail. However, because of poor economic conditions and the unreliability of the system—dirt was constantly interfering with the barcodes—the system was ditched altogether.

UPC Barcodes Enter the Market

So, whatever happened to RCA and Woodland’s bullseye barcoding system? RCA tried to implement it in 1967 at a Kroger Grocery store in Cincinnati, but the shape and size of the “barcode” limited the amount of data that could be encoded. Printing was also difficult, as any imperfection could render the system useless, and ultimately, it just couldn’t be adjusted to meet the needs of the store. There was also talk that whatever system was implemented, it would have to be standardized to satisfy not merely a single store, but the entire industry. The barcodes fell out of favor with Kroger Grocery and wouldn’t be used again.

RCA’s barcode concept attracted a lot of attention at the time, and the Ad Hoc Committee of the Universal Product Identification Product Code as well as an offshoot, the Symbol Committee, were formed to spearhead the development of a universal code that could be used across all stores. IBM kept working to find a better way to classify items, with the hopes that its bid would be accepted by the committee over RCA’s bullseye model. However, it wasn’t Woodland—still working at IBM—who designed the Universal Product Code (UPC) barcode. That distinction belongs to George Laurer, who designed a system based on the specifications of the committee: the barcode had to be small, readable from any direction, printable using existing technology, and there had to be fewer than 1 in 20,000 undetected errors. Ultimately, he came up with the rectangular, 10-digit barcode that is the UPC barcode of today. In 1973, Laurer’s UPC barcode was accepted by the committee, and it took a full year to implement in grocery stores. Famously, the first product ever identified with the UPC barcode was a pack of Wrigley’s Juicy Fruit chewing gum, scanned at Marsh’s supermarket in Troy, Ohio. A facsimile of the same pack of gum that was first scanned is now shown at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History as a testament to the game-changing nature of the barcode.

Barcodes Today

The barcode business boomed throughout the 1980s, and by 2004, 80% to 90% of the top 500 companies in the United States were all using barcodes. The healthcare industry is beginning to pick up on barcodes as well; in 2004, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) notified pharmaceutical companies that they were now required to have barcodes on certain medications. Today, many biobanks, research labs, clinical facilities, and hospitals have adopted barcode labels as a means of simplifying sample tracking and inventory and workflow management, and to reduce the potential for disastrous medical and scientific errors. Barcoding technology has come a long way since its inception, and now features 2D and even 3D barcodes as well as automated printers and labelers, laboratory information management systems (LIMS), and radio-frequency identification (RFID). The combination of all these systems has changed the way samples and inventory are managed, increasing the overall efficiency and productivity of labs.

LabTAG by GA International is a leading manufacturer of high-performance specialty labels and a supplier of identification solutions used in research and medical labs as well as healthcare institutions.